Dancing with my Camera

A Dream of Sadler’s Wells

My journey from photographing local dance schools to the main stage at Covent Garden

My journey from photographing local dance schools to the main stage at Covent Garden

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of the Royal Ballet. Francesca Hayward.

On January 15 2024 I walked down Floral Street, Covent Garden carrying my camera bag and tripod, and went in the stage door of the Royal Ballet and Opera. I was asked at the desk who I was here for, and I replied, ‘I’m here to photograph Manon on the main stage.’

This wasn’t just a journey that had taken me from the Northwest down to London Euston and across the tube to Covent Garden Station, but from photographing local dance schools, to professional companies over the past 20 years.

With Lorna Hill’s Wells series of ballet novels from the 1950s and 60s imprinted on my heart, I remembered how Sebastian helping Veronica get to her audition from Northumberland southbound to Colet Gardens, and shared her sense of relief.

Stepping inside a dance studio where young dancers learn the basics of ballet to incorporating everything they’ve learnt, and pushing beyond technique into artistry on stage, has been humbling to photograph.

From photographing feet in soft ballet shoes practice the five positions, while hands grip the barre in class, building strength and technique; to watching the studio rehearsal process where partnerships are tested and trust is formed; witnessing excitement and nerves in the wings before the dancer makes their entrance on stage and becomes transformed into their role; to making their curtain call at the end of a show alongside their company and conductor, all while the technical and artistic staff watch from the wings is such an adrenalin rush. For someone who doesn’t like the dark, this somehow doesn’t apply in the theatre, which feels like home. All I’ve ever wanted is to be able to point my lens at a stage and enter into the dancer’s realm. Even if this means travelling the length of the country for a fifteen minute stage call.

Whether I am photographing in the auditorium, or in the wings and backstage, the pain in my hands is lost to what I hope to capture on stage in that precious duration of a performance and sometimes I feel that I am dancing with my camera. To walk away after the applause with the music still in my head, hoping that I have got the shots I’d planned as well as unrehearsed moments is a jolt back to reality.

Travelling back home exhausted but elated, hot and sweaty from the exertion of photographing a full length production on a stage where the auditorium is kept warm for the dancer’s muscles, plus the heat of the lights on stage if you’ve been working in the wings. It really feels like you’ve worked as hard as the dancers. I download my pictures while I wash, sleep, don’t open my blind the following morning, switch on my computer and start the long edit.

I work through my RAW files to see what I got. I can’t explain the pain of not depressing the shutter at the right time for a leap, special moment in a pas de deux, getting movement in a picture when you didn’t want it, accidentally leaning against my tripod and taking a shot out of focus. It is exhausting to stand and hold still, all while following the movement of the dancers for an entire performance. We’re often reaching for painkillers with our water during the act breaks. In the wings, where you have to hand hold your camera, due to space and safety of the dancers, I come away feeling that I have dead weights at the end of my wrists.

The insecurities of a dance photographer are very real, and the pursuit of perfection is necessary but unhealthy at best.

I haven’t watched many ballets. Where I live in the Northwest you need to travel to the larger cities to see worldclass ballet. It’s not just the cost but I physically have to sit on my hands because I just want to photograph it. I really don’t find watching it relaxing, but more learning how the movement works from different viewpoints in the auditorium.

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of Sophie Gallie Dance Academy

My own experience of attending ballet class as a child was brief as I was told that I was considered too tall to take it further. I attended the Henleaze School of Ballet in Bristol in the 1970s, where I treasured my ballet slippers with their ribbons and pale blue leotard with its short frill, and was inspired by my teacher Joyce Harper who retired from teaching at the age of 97. I also remember being fascinated by an article about the Italian dancer Alessandra Ferri in Women’s Own magazine.

Following a degree in theatre studies and dramatic arts at the University of Warwick, I moved north to finish my education in journalism. Years later when my daughter began ballet classes with the Sutcliffe School of Dance, I started to take my camera with me with permission to photograph class, and rehearsals through to performance. I took class myself to learn correct ballet technique and know what to look for when photographing. A lot of ballet photographers today are ex dancers who are classically trained for this reason.

In time this led me to photograph the Northern Ballet School in Manchester, where I learned from the ex-principal Northern Ballet dancer and choreographer David Needham, as I photographed my first full length production of Swan Lake. David had spent several years coaching and choreographing in America where he worked with the renowned Laura Alonso, who invited him to visit Cuba to teach where he was appointed Artistic Director of Western Ballet Theatre of Puerto Rico.

I remember arriving at Oxford Road train station in Manchester, quickly picking up some English National Ballet flyers at the Palace theatre, before making my way to the Northern Ballet School, and discovering its beautiful art deco studios and theatre.

I learnt so much here and got to experience working alongside dedicated students who had come from all over the world to train. I anguished about where to work and sit in the auditorium (the stage was near the floor with no pit), experimented with different shutter speeds and worked with them through to their dress rehearsal. I still have a swan feather I picked up from the stage floor.

I’ve now learnt that to photograph ballet in a proscenium arch theatre, with an orchestra pit, it is best to work centrally in the auditorium and to stand so that you are working at waist level to the dancers on stage. This doesn’t always happen if the technical team’s lighting desk is still in the auditorium complete with wires hanging down. Most dance photographer’s like to work slightly off set centre for more flattering pictures.

I remember one of the dance teachers Shannon Parker, who had danced with San Francisco Ballet, and was teaching the swan corps the challenging technical choreography.

The students had just returned from lunch for their afternoon rehearsal on stage and were stretching and letting their feet breathe before putting their pointe shoes back on. There was lots of groaning because the rehearsals are hard, then Miss Parker walked to the front of the stage ready to lead the rehearsal, and told the girls how privileged they were to get to train as dancers and perform in this ballet. She reminded them not just that others would love this opportunity, but that people were fighting in wars around the world. This struck a chord with me. Every time I walk into a theatre to photograph dance it means everything to me.

This also reminds me of Catherin Bruton’s moving children’s novel No Ballet Shoes in Syria, which follows the story of Aya who arrives in Britain with her mum and baby brother, seeking asylum from the war in Syria. After discovering a local dance school, her talent is encouraged, while they fight to remain in the country and find out about her missing father.

While writing this, I have recently worked with London City Ballet who included Alexei Ratmansky’s Pictures at an Exhibition in their 2025 tour. In an article Ratmansky described how the Ukrainian dance companies continue performing with only half of their dancers, and when there’s an air-raid, they go to the shelter with the audience and then continue the performance after when they get the all-clear. He said, ‘Your voice matters. If you don’t defend what you value – the democracy, the ideals – then it can be gone.’

I continued to work with this school for nearly 15 years photographing their repertoire of Giselle, Coppelia and The Nutcracker and other dance shows, and longer alongside David at The Hammond school in Chester. I would be so excited to see what picture they’d use for their next ballet poster, and on one occasion as I was walking down from the station and turned the corner towards The Dancehouse, home of the Northern Ballet School, I saw a pennant banner of Giselle with my picture that I was on my way to photograph.

David has an intense eye for detail, and I loved watching him rehearse the students on and off stage correcting and congratulating, sharing stories from his past, and demonstrating stage make up with his toolbox filled with old sticks of Leichner and the process of selecting costumes. He is also very kind and would take time at the end of a long rehearsal, to plot beautiful stage pictures for me to photograph.

Two years later in 2010 I didn’t just stop off at the Palace to collect flyers for English National Ballet, I was able to enter through the stage door as Wayne Eagling gave me permission to photograph the dress rehearsal for Romeo and Juliet with Vadim Muntagirov & Daria Klimentova. My first professional ballet shoot. I prepared for it by learning the choreography (a practice I always do where I can before a shoot) from Wayne and Alessandra Ferri’s balcony pas de deux from 1984 on YouTube and endlessly listening to Prokofiev’s score.

This was a dream come true for me, but I learned after that I should have worked alongside the press photographers in the auditorium not escape to the circle, where I was to discover the artistic staff sat to write corrections, to be disciplined enough to press the shutter at the most heartbreaking moments, and that my camera gear wasn’t good enough for theatre photography.

This production was Rudolf Nureyev's staging from 1985. He had the role of Romeo created on him by Kenneth MacMillan back in 1965 where the emphasis was more about Juliet’s dramatic trajectory, danced by Margot Fonteyn. And while Nureyev’s choreography was to show her as more of a rebel, he naturally paced the emphasis on exploring Romeo’s role. He took Shakespeare’s text to heart and included scenes where Juliet dances with ‘death’ as she has a premonition of her wedding with death where she wakes up to discover a skeleton lying on top of her. The lovers are physically shown as ‘star-crossed’ in the bedroom pas de deux choreography, but what stayed with me was a sensually wrought pas de deux between Romeo and Benvolio as Romeo wrongfully discovers Juliet’s fate. This was choreography only Nureyev could have created, and a young Vadim danced it magnificently.

This was the beginning of a love affair for me with ballet photography, and as with all matters of the heart, I was about to learn to face rejection over and over again. Ballet photography is a discipline in the same way as dancing, but gaining access to photograph at a professional level is brutal, and the reason why so many ex dancers turn to photography as they already have this trust within a company and can access all areas. I also needed to improve my gear for a profession that many do for the love of it.

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of Birmingham Royal Ballet. Delia Mathews

A year later I was allowed to attend the générale (dress) rehearsal for Birmingham Royal Ballet’s The Nutcracker, and also Northern Ballet’s Giselle where I met Dance Europe’s editor, photographer and ex dancer Emma Manning. She was an inspiration, and while giving me advice leaving the dark theatre after photographing the rehearsal, I almost walked into the glass door. She hand held her camera while working, which she put in an ordinary bag at the end and got back to the train station in record time. I also went onto photograph the première of David Nixon’s production of Beauty and the Beast.

Working with Birmingham Royal Ballet has been so inspiring. I began photographing with them when Sir David Bintley was the artistic director and now with Carlos Acosta and witness different styles of leading a company.

The following year I got to work again with English National Ballet when Tamara Rojo became the artistic director, and they staged The Sleeping Beauty at Milton Keynes Theatre. Some of my images were later used on the cover and inside the programme as it toured. Later that year I joined the company again for The Nutcracker at The Mayflower in Southampton and all my Christmas wishes came true when my image of Daria Klimentova and Vadim Muntagirov was used as their Christmas card. The following year when this production was touring at the Liverpool Empire, I remember crossing over from the train station to see some of my images used as decals on the front of the theatre. These moments would stop me in my tracks and were everything to me. They also used my images in Dancing Times magazine to accompany reviews and I can’t explain the feeling when it would arrive through my letterbox.

During 2013/14 I experienced photographing at The Royal Albert Hall in English National Ballet’s production of Swan Lake in-the-round choreographed by Derek Deane and also Romeo and Juliet. Working in this incredible theatre and adjusting to photographing differently as the dancers presented to three not one side was a great experience.

Derek Deane’s Swan Lake in-the-round transforms the Royal Albert Hall into a magical lake. This is the perfect setting for this ballet, as Derek’s beautiful choreography makes the audience feel like they involved in the action as they surround the lake so close to the 60 swans. Tchaikovsky’s score, played live by the English National Ballet Philharmonic, fills the auditorium and you’ll never want to leave.

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of English National Ballet

After travelling from Preston by coach I arrived in London to photograph Swan Lake in-the-round where I was to meet Frederika Davis, one of the pioneers of modern ballet photography, at an Arabic café opposite Harrod’s for afternoon tea with exquisite warm miniature scones, before she hailed a taxi to take us to the Royal Albert Hall. I had got in touch with her through the Royal Ballet in 2011 after seeing her pictures in Dancing Times magazine. She was kind enough to share her knowledge and advise me about attempting to become a dance photographer. She was much taller than I’d anticipated, extremely elegant and full of exotic stories.

As a child Frederika had a great interest in photography and dance and took ballet classes from an early age. As an adult her interest in ballet was fostered by her husband an acquaintance of Alicia Markova, and by watching dancers in the studio of Audrey de Vos where her daughter Sasha took classes. She started to photograph dance, especially the Royal Ballet, and was very active during the sixties and seventies photographing ballet live on stage and in class, breaking free of the studio shots that were taken before.

She photographed Fonteyn and Nureyev just after he defected to the West, and the pictures in her archive act as a record and will keep alive this amazing partnership.

A change in personal circumstances led her to retire in the mid 70s but, in recent years, with the advent of digital cameras, she returned to her old favourite occupation and continued taking photographs of the Royal Ballet and other companies in rehearsal well into her nineties. Her work was regularly printed in Dancing Times and other dance press. And true to form she embraced the digital revolution and learnt editing skills.

‘Advice on becoming a ballet – or should I say dance photographer, because ballet is only part of it. I am quite surprised that I became so successful because like you it started through the love of dance and through seeing performances in London from 1944. In those days my husband and I went sometimes three times a week and watched the Royal Ballet grow from the little company which was Sadler’s Wells Ballet.

‘Each of us dance photographers got into it a different way through a different path. My daughter, Sasha Davis, started ballet classes at the age of four and later went to the Royal Ballet School, which gave me the opportunity to photograph in my home made studio, some of the students and young dancers from the Royal Ballet. This led to an invitation from the press office at Covent Garden who saw some of my efforts, and about one month later Nureyev defected, and as I was now on the Royal Opera House list I got everything he and Margot did together. Sasha then got into the Royal Ballet. So I am very ballet connected and a lot of it is good luck and who you know. One of the things you have to make up your mind to is that you are NOT going to make much money! Dance magazines are short of cash and dancers and dance students do not have a lot of available cash. The greatest dance photographers of my time made a living out of other things. Tony Crickmay was a society portrait photographer, Mike Davis did a lot of commercial photography and girl’s annuals – Reg Wilson had a gun shop and others worked in other branches of photography to make a living.

‘You have the right attitude if you think of it as something you love and just go on taking every opportunity you have to take dance photographs. So much of this is luck. It is a great deal more difficult to break into the big scene now than it was in 1960 when I started. I am now 87 and started digital photography four years ago after having retired for years. I went to learn the other half of digital photography – Photoshop when I was 80 years old at the local poly. It is essential for composition and cutting out odd legs and arms and sharpening etc. For theatre work it is essential that you have a 200mm telephoto lens which goes down to at least aperture 2.8, and for action you usually cannot get away with less than a 250th second speed to get crisp shots, though in the black pictures you have to break all the rules! Also, continuous focus is best.

‘I think it also helps to be nearer to London as most of the action is here and one is able to run off to any photo call that you have managed to access. Just go on taking photos just as long as you ENJOY it – most of us dance photographers do it for that reason however great they are.’

She taught me to have an attention to detail and discard shots that weren’t technically correct of the dancer. ‘There are a number which I would not have shown with details like floppy feet and other small details. I am very ruthless chucking out more than I show – if I think so much as a finger is wrong. At the speed we have to take the shots we are bound to have many which are technically wrong or sloppy – not necessarily because the dancer was bad but because we snapped at the wrong 250th/sec. Inevitable! Also cutting out background and bringing the main figures as the important part of the finished composition.

‘It is terribly hard work because you have to get home from the photo call, immediately run through the shots – edit them and send them the same evening. Some of the guys have a laptop with them and send straight out of the camera in the interval. I have never worked that way and it also accounts for photos which sometimes are not so good. Being a ballet photographer is tough but fun!

‘You must have a very steady tripod. If you are getting shake you need a lens with a stabiliser. You certainly need one if you are going to hand hold a telephoto lens because of the weight or if the tripod is not very steady. If you have the stabiliser then use it when you feel shaky instead of tying up the camera, but remember your batteries will not last as long and the focus takes a little longer to change.

‘Regarding light – one must be prepared to make use of any light available, and in dark situations particularly, I play around with the ISO settings as much as with the aperture settings. Most photographers use two or three cameras with different lenses as well as the main 200mm lens. I cannot carry so much weight at my age struggling on London tube trains (driving with the present London parking problems out of the question)!

‘I often favour a side position at Sadler’s Wells where there is very little curve to the theatre and where there is that little row of seats raised at the sides. This raises my camera up to stage level and I get a slightly different view to some of the other photographers. But it does depend on the plan of the auditorium. I must repeat that to have a camera with very high ISO settings is really essential. They think photographers are magicians!

‘Presentation and composition are very important and where a lot of the press photographers fall down. The dancers are the centre of attention and the main focal point which people want to see and which you should draw attention to. You only learn by experiment and experience.

‘Being a dance photographer is very specialised if you really know anything about it. I find my 70-200 mm lens covers everything needed from the positions we occupy in a theatre. Any further closeness needed can be done on Photoshop or Elements. I find your editing programme is really the other half of digital photography. A tremendous part of the shots looking good is to have good cropping, based on the rules which apply to composition in painting, and to know which bits to cut out and which bits to bring into being the main subject. I have rescued many a so-so image with good editing and this technique I used to do in the dark room also.

‘The one thing I cannot give you is the good fortune to have been around in the time of Margot and Rudi which gave me the opportunity of getting known, and today it is very difficult to break in as so many people can take good photos with digital. The competition is enormous. Just keep enjoying it and taking pictures.’

I will miss receiving her home printed ballet Christmas cards but I am so grateful to have known her.

With Romeo and Juliet the court scenes swirled around the audience, the fights were exciting as they were so close you could see the sweat on their costumes, but it was the intimacy and intensity of the lovers that moved me and how small they appeared alone on the stage abandoned by their world.

I’ve often thought how beautiful it would be for a Nutcracker in-the-round production. For it to snow on the Snowflakes dancing in the oval auditorium would be magical to see live.

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of English National Ballet

I have always been interested in production rather than studio photography. The thrill for me is capturing that moment in ‘real’ time. Sometimes I have to wait years before I get the chance to improve on a particular moment that I may have missed in a previous shoot. I’ll also work with a recording where possible, and break down the choreography, and take screen shots of particular moments or details that I would like to photograph.

Companies often have a list of photographers they work with for press and marketing purposes. Working in a theatre alongside press photographers can be daunting. The commissioned photographer (and videographers) sets his gear up before the rest of the photographers are allowed in the auditorium, and then it can be difficult to secure a good shotting spot. So many times I arrive first at the stage door and somehow always manage to be last in the auditorium! I believe that our brains are wired certain ways, and for me if I can’t work centrally, my offset default is from the right facing the stage.

I have found some photographers to be very helpful with advice over the years. Working alongside Bill Cooper was always very special. Last year I got to meet Asya Verzhbinsky at the Manon photocall after she had been kind enough to reply to my email years before, and learn from Rachel Hollings’ artistic insight.

Gene Schavione said that basically we need to learn how to see and photographic in the dark. He made me smile in response to my email when he wrote, ‘Of course the challenge is always dramatic lighting – which often means no lighting.’ He said that while he is officially retired from American Ballet Theatre after 20 years he still misses creating images, and that he’s ‘currently working on a book to prove to myself I was here.’ This made me a little sad, but we are the figures in the shadows trying to capture the light.

After discovering that dancers often didn’t have pictures of themselves performing, other than production and press stills produced for the programme and posters, I give them images because I think there’s no point them sitting on my computer. If I’ve ‘taken’ a photo of them, I want to give back. Theatre etiquette only allows members of the public to take pictures during the curtain call, so as not to distract the dancers while performing, or put out a picture that is not technically correct or flattering to the dancer which could affect their career. Now with phone cameras and social media this has changed but there is still no photography allowed during the performance.

If I’m photographing from the auditorium with the rest of the press photographers, it’s usually the générale rehearsal, where ‘friends’/donors are allowed to be present and hear live corrections given to the dancers by the artistic staff. They sometimes also watch company class on stage.

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of the Royal Ballet. Mayara Magri

In 2015 I photographed English National Ballet’s Swan Lake at the London Coliseum with Alina Cojocaru & Ivan Vasiliev, and it was interesting to experience the difference photographing Derek Deane’s production in a proscenium arch theatre this time.

I always get very distracted photographing Swan Lake because ideally I’d like to photograph one performance concentrating on the lead principal’s performance and another with my focus on the incredible work the corps de ballet do.

The preparation these dancers undertake for what is commonly considered one of the most difficult ballets to dance, often in large warehouses, is nothing short of drill. While the audience see the beautiful headpieces and tutus, these dancers play many different roles during the ballet. It is exhausting for them as they are leaping one minute and the next holding a static pose for what must feel like eternity. They are the ballet and have to learn to breathe as one to create the incredible formations the choreography demands.

Vasiliev is a great virtuoso dancer, and I felt he was a little restrained by the role of the prince, but the passion be brought to his role to save Alina as Odette was impressive. Alina always brings emotion to her dancing, and while she must have danced this role hundreds of times, she demonstrated the character’s despair and was dazzling in the dual role of Odile.

Photographing this ballet began an ongoing Study of Swans for me. I find it fascinating how the dancers embody the swan’s long neck with the placement of their arms and hands and how they move so gracefully together. The most beautiful image I attempt to capture, is when the dancer bends over on the floor, with one leg tucked beneath her the other extended in front, with her arms crossed over her foot and her head tucked down like a sleeping swan resting on the water. When the stage fills with dry ice the stage floor transforms into the lake, and the effect is so achingly beautiful and there is a desire to drown in Tchaikovsky’s score.

There are many dark sides to this story driven by Rothbart’s evil spell, another exhausting swan role as he dances fiercely with his large wings forcing the swans to obey him. I think it’s interesting that swan’s main predator are humans, who hunt them as demonstrated by the prince’s eagerness to hunt.

I also had the opportunity to photograph one of the company’s studio Romeo and Juliet rehearsals of Juliet’s solo at Markova House, with Alison McWhinney & Shiori Kase. After travelling by train from Preston to London and navigating the tube, I worked in the Paul Clarke Studio and it was fascinating to see how these two dancers approached the tortuous scene where Juliet finally decides to drink the potion that will make her appear dead, to buy time for Romeo to return and take her away with him, instead of her arranged marriage to Paris which would make her a bigamist.

I find the role of Juliet very raw. She’s so young, not quite ready to leave her childhood behind, but discovering herself alongside society’s expectations, and then she falls in love for the first time. She experiences such overwhelming feelings for Romeo and tries to follow her religious path by marrying him secretly, but her father and family make it clear that if she disobeys, she will be cast out and left destitute.

During this time, she also witnesses her mother’s despair when her cousin Tybalt is killed, and has to equate her grief for him with that of her lover at whose hand Tybalt died.

In a desperate bid to join the now banished Romeo, she follows Friar Lawrence’s advice by taking a poison that would make her appear dead but wouldn’t actually kill her, to allow time for Romeo to rescue her from her arranged marriage to Paris.

Her family are angry and grieving, her childhood nurse cannot help her, and she doesn’t know where Romeo is other than he is banished from Verona. Her isolation must have been so hard to bear as she dared to take her place in the family crypt. She chose love and ultimately death.

In moments like this the outside world disappears, as your focus shifts and the artists in front of you not only just take you back to a different time and place but deep inside your emotions. Leaving the building can be such a shock to return to the real world, but the hundreds of pictures on your memory card give the return journey an urgency to begin editing and hopefully do justice to what you have photographed.

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of English National Ballet. Alison McWhinney

I received my first professional commission from Birmingham Royal Ballet in 2016 to photograph An Evening of Music and Dance at Birmingham Symphony Hall. This was a difficult job as I had to give equal weight to the musicians as well as the dancers and be everywhere in the auditorium to capture the full orchestra, detailed parts of it, and the dancers. I got to work alongside their design executive and conductor Lee Armstrong, who was great fun to work with, and inspired me with wanting to do the musicians justice.

At school I had taken violin lessons, with Mike Evans who played the viola solo for Ultravox’s Vienna, and soon discovered that I much preferred listening to him play than the sound I was making myself! But I’ve always loved music. And the following year on 10 March I attended the generale for the world premiere of Northern Ballet’s Casanova choreographed by Kenneth Tindall to a score by Kerry Muzzey, which was to be one of the highlights of my career. I had never experienced anything like it. It was so powerful and innovative, I was obsessed.

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of Northern Ballet. Pippa Moore & Javier Torres

As I have developed, I knew that the highlight of every ballet for me was photographing the pas de deux. As Nureyev said, ‘A pas de deux is a dialogue of love.’ But the pas de deux between Bellino and Casanova in the second act nearly stopped my heart. It is one of the most beautiful pas de deux that I’ve ever photographed. I don’t think I have ever been so affected by dance as I was with this.

Kenny has re-invented himself from the role of dancer to choreographer having worked with Northern Ballet since 2003 before retiring as a premier dancer in 2015 to choreograph. The idea to create a ballet of Casanova’s life had been living in his imagination for years.

Along with Ian Kelly (biographer of Casanova), I believe they have changed history’s perspective on this man and righted a long standing wrong that saw him as a libertine with a talent for survival. They have given him the respect and understanding that he so dearly craved. And his journey has taken a man, who was reportedly born in the wings of a ballet, to a ballet about his life to put him to rest.

Kenny questioned, ‘How do we distil this man, how do we capture the essence against the backdrop of this incredible period?’ This is a narrative ballet that has to capture Casanova as best as possible in 100 minutes.

‘I really didn’t want the curtain to go up and there to be an old man sitting at his desk with Vivaldi playing. It was really important for me to be able to evoke the worlds of the 18th century, the masquerade, the musicians, the church, the gambling halls, the rigalottos, these are something you can viscerally enjoy and be part of.

‘I wanted all the pointers to be in the right 18th century direction and to be correct. This is why I brought in an 18th century specialist to see how we could take a fresh perspective on that, and how we could deconstruct a period and the look of the costumes, and try to inject it with a modern edge so that it would appeal to a mass audience and bring this man to as many people as possible. Show you something you didn’t know about him, from his time as a priest . . .’

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of Northern Ballet

There are three significant pas de deux in the ballet; Casanova and M.M. an aristocratic nun in Act One, the pas de deux with Bellino, and that with Henriette in Act Two, each representing different aspects of Casanova’s relationships throughout his life. Giuliano Contadini, the dancer Kenny built Casanova on, described how the pas de deux with M.M. , ‘was purely sensual and very athletic to enjoy with enthusiasm and fervour. The music is absolutely incredible and gives the perfect balance of power and melody.

‘Bellino was the love for someone that is also your best friend, which happened to be the case for the actual dancer playing Bellino (Dreda Blow). We joined the company together and truly are best friends, and I guess that translated in the pas de deux, as I never felt so in sync and at ease dancing with another girl in my career. There was total trust and abandonment. And the music captured that perfectly.

‘Henriette is the love of Casanova’s life, the one he will never forget. I remember rehearsing the pas de deux in the early stages and just crying while listening to the music and watching Henriette (played by Hannah Bateman) tell the story of the baby she buried, and the one she left behind to escape her abusive husband. This pas de deux is intimate and delicate, and the music transpires sadness and hope for someone to come and rescue you and tell you everything is going to be ok, which is something we can all relate to at some point in our lives.’

The first pas de deux in Act One is with Casanova and M.M. the mistress to Cardinal de Bernis. It is set in the Cardinal’s luxurious private apartments. Following the instructions on the note, Casanova arrives at the apartment and M.M. sets about a staged seduction for the benefit of her hidden lover, the voyeur de Bernis. They are interrupted by Bragadin who warns Casanova that the inquisition is coming for him.

This role was created around Ailen Ramos Betincourt who said, ‘This dance has been the most daring I’ve done. The music helped a lot, I only had to hear the first note of the pas de deux, and I went completely into character. It set the atmosphere for the scene and was excellent sublime work of the composer.

‘Kenny knew exactly what he wanted in this pas de deux. He had a clear idea, but of course the three of us we went looking for and finding the most appropriate form, movement and details.

‘I prepared myself physically, the choreography, and the costumes demanded it. I liked the big and imposing white hat (wimple), but to dance with it on would have been uncomfortable, but I take it off right at the beginning of the pas de deux.

‘For me the Casanova ballet, and of course this pas de deux was very special. I would dance it every day of my life, and I will carry it with me always . . . it really marked me.’

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of Northern Ballet. Abigail Prudames & Joseph Taylor

The second pas de deux in Act Two shows Casanova situated in Paris with his benefactor Madame de Pompadour. Intending to throw a party, he auditions musicians, and amongst them is his old acquaintance Balletti. Bellino is also hired and Casanova, uncertain of her true gender, is intrigued by her. She admires Casanova’s serious interests as a writer, and in turn reveals that she is a woman.

Kenny described this pas de deux in Act One with Bellino and Casanova as about masks - hiding the truth - and trust. ‘Masking and hiding was definitely a strong motif throughout the ballet. Bellino is masquerading as a Castrato, hiding her true self which is what fascinates Casanova when they meet. Movements that hide/reveal, open/close, trust/guard became an important springboard for creating those duets.’

Dreda performed the second pas de deux with Giuliano approximately 40 times and described the exceptional off balance back bend moment as both terrifying and exciting. She said, ‘It got less terrifying and exhilarating as time went by and we knew the mechanics for it to be safe. I could then let go of the fear and really indulge in the moment and it became fun. I was in good hands with Giuliano though. He would never let me fall, never let me hurt myself. I just had to be brave.’

Kenny explained how, ‘Eventually what happens in this relationship is he sets her free to be a woman, to be a soprano singer, which is a beautiful side to Casanova. That he’s not a bed notch libertine, but someone that actually elevates and helps women to move onto the next stage. That was a really important part of our story to tell.’

Dreda said, ‘It took me a while to get used to the costume (and the cod piece!) but I knew it was right for the show and the character, and I embraced the novelty of it. It wasn’t very comfortable to dance in, but of course the bulk of the duet was done undressed! Richard Mawbey’s wig design changed a lot. The original one was twice as voluminous! But the final version of the wig was stunning. I loved it and felt great in it.’

Northern Ballet’s artistic director David Nixon OBE described Casanova as the ‘most elaborate wig ballet in the history of ballet since Louis I think.’

Dreda described how, ‘The music told the story so beautifully for this duet. We just needed to ride the wave of energy. It was so powerful when played by the orchestra – it gave us everything we needed. It carried me night after night, show after show!’

The third pas de deux in Act Two is with Casanova and Henriette. Casanova stumbles into Henriette, who is dressed as a soldier, in order to run away from an abusive husband. Casanova offers her shelter and they become lovers. They are interrupted by Madame de Pompadour who has set up a meeting for Casanova with Voltaire. Casanova begs Henriette to wait for him, convinced he has at last found his perfect partner. She is torn between her love for Casanova and that for her children. In his absence Henriette’s husband arrives and forces her to leave with him. Casanova returns to his apartment to find Henriette gone with only a letter left behind. Despondent, he attempts to escape into the world of sensuality. Henriette unexpectedly returns and, finding her worst fears about men confirmed, rejects Casanova forever.

This role was created with Northern Ballet’s principal soloist Hannah Bateman who is married to Kenny. David Nixon said how Henriette – Casanova’s greatest love – is probably being danced by Kenny’s greatest love.

Hannah said, ‘Working on Casanova was incredible! Kenneth is a very unique talent, a natural leader with a very strong physical style of choreography. He has an immense capacity for seeing and taking care of the smallest detail and always keeping in mind the overall project. He is completely immersed in the work, music, design, lighting and feel for the world he is creating. By the time he comes to the studio you are tasked with breathing life into characters that have been living in his imagination for years! The responsibility is huge, but he gives over such trust in his team and dancers. It feels like a privilege to be part of it all.’

‘For Henriette I needed to be fully formed and in a state of crisis the minute she enters the stage. You are also responsible for maintaining and building the atmosphere from where Bellino has left it, so you have to step up and support Casanova and the ballet. Her storyline is tragic and has to come from a place of truth. It was emotionally draining, but theatrically satisfying, and exactly what we dancers love! I like to think of Henriette as a feminist before her time. What an absolutely awful situation she found herself in . . . the trappings of the patriarchy. Casanova was at least support in an otherwise dark and lonely existence.

‘Casanova was one of the greatest experiences of my career and life’ continued Hannah. The whole company was completely in tune with each other. We had this brilliant team all around us. Kenny was a dream leader, supported by Christelle Horna and David Nixon, both of whom are incredible coaches and inspiring in the studio. I have a vivid memory of the last show in London. The applause was like nothing I’ve experienced . . . my eyes filled with tears because I was living my dream and I was sharing it with a beautiful group of people. Giuliano looked ethereal with joy as did Dreda, and David Nixon was applauding wildly in the wings and looked proud of his company. Even now when I think of it, I can physically connect to that time and it washes over me with pure warmth, happiness and achievement.’

This made me to question why so many dancers left the company after performing in this ballet. Giuliano left the company to become a massage therapist; Dreda left to do new things and move back home to Canada to be with her family; Ailen went back to Spain and Lucia Solari (who also danced Bellino) left to join Ballett im Revier. Hannah and Kenny became parents.

Is it a case of as well as being the greatest performance of their careers, that it took so much from them, that they had to move onto different things to enable them to step back from such emotion? Or that they had all given everything they could, and nothing would ever be the same?

I got to photograph the ballet again when it came back into Northern Ballet’s repertoire five years later. I went to photograph that incredible pas de deux in a studio rehearsal, and as I was setting up my tripod, I looked around the room and discovered three dancers for the role of Casanova would be rehearsing with a fourth watching!

Since then Casanova has continued to tour across America and I was honoured for some of my production stills to be used on the CD sleeve of Kerry Muzzey’s symphonic score.

I also recall being so excited to show a new wide lens I was trying out to the press officer at the dress rehearsal, that I fell (twice) up the low steps at the side of the auditorium in Leeds Grand Theatre. I badly sprained my ankle, but my lens was spared. It was a double rehearsal with two different casts so I was in a lot of pain by the end and had trouble removing my trainer.

The worst accident I’ve had while photographing was in The Dancehouse theatre, where the stage finishes close to the floor in the auditorium. There is no pit. I was set up for a double rehearsal day in the auditorium and my camera was thankfully on my tripod, and I climbed on stage to have a chat with the stage manager before it began. It was quite dark as there were only working lights on, and returning to the auditorium, I missed my footing stepping down from the stage and spun off taking out some of the front row of seats.

Lying at the bottom of the stage at first I couldn’t feel anything and thought I had paralysed myself. Then the stage technicans came to check on me and I realised that I had two shows to photograph and things had begun to hurt. Fortunately, on this occasion, I’d mainly damaged my left hand, hip and some ribs and photographed with a damp tea towel on this hand. Surprisingly, I was quite pleased with my pictures but got grief at the hospital a few days later when I got checked out (after finishing editing my work). These dress rehearsals can’t be repeated, so you have to push through the pain.

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of Northern Ballet. Javier Torres

Other ballets that have held a special place in my heart are Northern Ballet’s Wuthering Heights, Dangerous Liaisons and The Little Mermaid choreographed by David Nixon; and Cathy Marston’s Jane Eyre. This company produce amazing narrative ballets.

Birmingham Royal Ballet gave me my first experience of pas de deux studio rehearsal photography, with a Romeo and Juliet pas de deux rehearsal with Mathias Dingman and Yaoqian Shang, led by then répétiteur Dominic Antonnuci. This was followed by The Nutcracker pas de deux rehearsal, with Cesar Morales and Karla Doorbar and Momoko Hirata, and Yasuo Atsuji and Samara Downs led by Michael O’Hare and Wolfgang Stollwitzer. I wanted to capture the beauty of the transition scene at the end of Act One before the start of the snowflakes, where Clara and the Nutcracker Prince dance the most beautiful pas de deux almost in darkness until the stage gradually lightens for the Snow Fairy’s entrance in a well lit studio. And Beauty and the Beast pas de deux rehearsal with Maureya Lebowitz & Yasuo Atsuji (with David Bintley & Dominic Antonucci). Sometimes the Benesh notator is present at a studio rehearsal, to ensure that the choreography is delivered true to the original performance when it was first noted down. I learned shorthand as a journalist but Benesh Movement Notation is an art in itself.

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of Northern Ballet. Abigail Prudames

In June 2018 Jenna Roberts invited me to photograph her final performance of Romeo and Juliet from the wings and her final curtain call with Birmingham Royal Ballet. I was so honoured but also nervous as I had not done this before. It was a boiling hot summer’s day, and my train was delayed, but I got there on time. I didn’t realise that I should have worn dark clothes for working in the wings or that I could only photograph Jenna and a few other dancers who had agreed, which made things difficult. I can’t tell you the pain of standing in the wings, with my camera, unable to take pictures.

I had to leave before the bedroom pas de deux, also very difficult to do, to position myself for the flower throw at the back of the auditorium in the lighting box behind Perspex. I knew that I wouldn’t get much from there, and the moment Jenna appeared behind the curtain I ran to the front of the auditorium to get my shot, as the audience rose to their feet in a long standing ovation, and then followed me to the front on the pit!

Fortunately, I was invited back to photograph Birmingham Royal Ballet’s new season launch with Carlos Acosta in 2019 and photographed the Swan Lake pas de deux Momoko Hirata and Cesar Morales accompanied by Robert Gibbs on the violin and a pianist which is such a special memory.

At the end of 2019 I was allowed back in the wings to photograph the Waltz of the Snowflakes from The Nutcracker Act One. This was something I have always wanted to capture as it is one of the most beautiful and loved parts of the ballet. The waltz only lasts for seven minutes and twenty-two seconds. It is also very fast, so blink and you’ve missed it! At the end of the scene, as the snowflakes make their final formation across the darkening stage, I pointed my camera up to capture the flakes falling from the flies and it gave the stage an ethereal quality that I never wanted to end.

From the wings, shooting across the lights, shows the whole spectrum of diffuse white light in a magical display of pinks and blues. While snowflakes appear fragile when they are falling in nature, you have to look at what they can do when they stick together.

I’ve continued to chase snowflakes for many years now and have added them to my study of the incredible corps de ballet. I look forward to the end of the year to be able to return to photograph them in Birmingham Royal Ballet’s The Nutcracker, which I never tire of because like snowflakes, my Christmas memories gather and dance each beautiful, unique and gone too soon.

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of Birmingham Royal Ballet. Lucy Waine

For me the best way to show the emotion this scene evokes in me, is a scene from Alfonso Cuaron’s 1995 film A Little Princess, starring Eleanor Bron as the presumed orphaned girl Sara Crewe. She had lived in India with her widowed father, but when he is called to serve, Sara is sent to the boarding school in New York where her late mother had attended. She is told her father has died in the trenches and Sara stays on as a servant at the school. At the end of the film there is a beautiful scene when Sara wakes in her attic bedroom and walks in a trance towards the window which has blown wide in a snowstorm. Across in the opposite house Ram Dass, the neighbour’s Indian associate faces her and lifts his arms to encourage Sara to copy him, and she dances and swirls in the snowflakes awaking feelings of happiness and hope. She later discovers that her father has survived, and they are reunited.

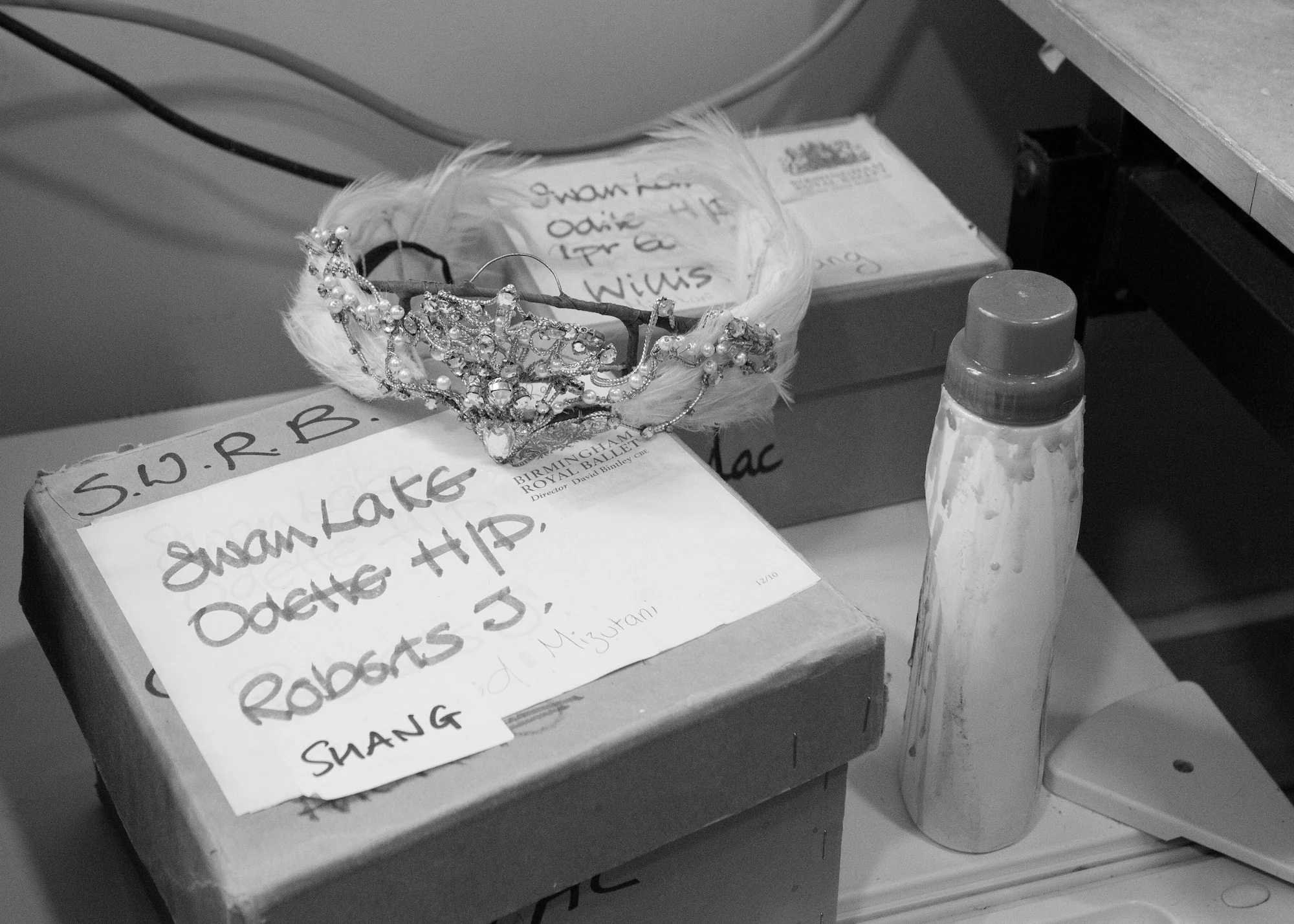

The following year I photographed Birmingham Royal Ballet’s Swan Lake from the wings with principal dancers Miki Mizutani and Lachlan Monaghan. This was the start of a special collaboration of my working with Miki.

I’d always found Birmingham Royal Ballet’s production very dark to photograph from the auditorium and hoped there would be more light to capture the swans up close from the wings. I remember focusing on light and shadow and the stillness of the corps members in between. I was particularly struck by Eilis Small who appeared to me like a Degas sculpture in her composed stillness.

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of Northern Ballet. Ayana Kanda

Then Covid hit, and the theatres closed. I remember photographing a show with the Northern Ballet School, having travelled into Manchester Oxford Road station on a strangely empty train, and the stage manager crying at the end of the performance because no one knew if their jobs would be there for them after the pandemic. My first production following the pandemic was with Norther Ballet’s Dangerous Liaison’s at The Lowry theatre in Manchester. While waiting to go in the theatre, desperate to photograph again, I couldn’t understand why so many people wearing legal outfits and wigs were coming and going and later discovered that they weren’t rehearsing for a play as I’d previously thought, but the space had also been commandeered as a makeshift court.

The production was performed as a black box production, with minimal dancers, set, costume and lighting to keep the dancers and technicians safe from exposure to the infection. I like this minimal style of working as nothing distracts from the dance. There was just me, the artistic director and choreographer David Nixon and the press person all wearing masks. When I came out afterwards, I felt overwhelmed by emotion to have photographed again.

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of Northern Ballet. Ayami Miyata & Riku Ito

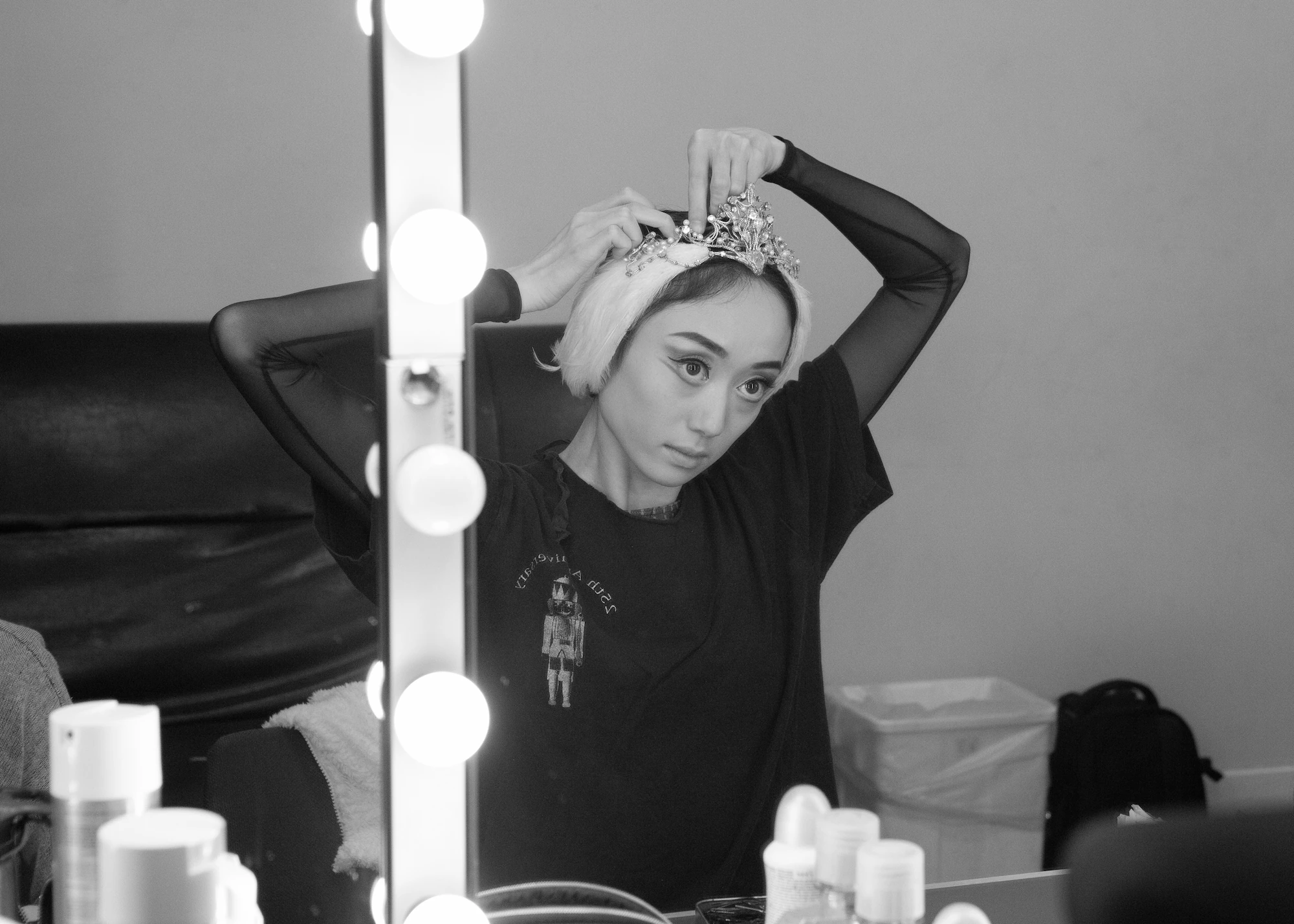

At the end of 2022 I photographed Birmingham Royal Ballet principal dancer Miki Mizutani backstage preparing for her role as the Sugar Plum Fairy in The Nutcracker and from the wings. This involved getting my head around working with no natural or stage lighting and depending only on strip lights. There is an intimacy, camaraderie and great sense of fun working in the changing rooms and corridors leading to the stage.

Dressing rooms can be very cramped, and it is a very personal way of photographing involving trust and intuition. Dancers can be nervous, follow certain rituals, and you need to know when to give them privacy and space. They need to get made up, do their hair, have costumes ready, warm up and stretch, and decide on which pointe shoes to dance in. All while keeping an eye on the television screen showing them the action on stage so they don’t miss their entrances.

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of Birmingham Royal Ballet. Miki Mizutani

Dancers do their own make up, from being taught at school that their eyes need to be seen from the back of the gods and sometimes copying from a photograph taken of an earlier performance. I photographed Birmingham Royal Ballet first artist Rosanna Ely demonstrating how she put on her make-up before a performance to a group of school children, and she said how they must all remove their make-up off before leaving the theatre however tired they are because their make up is not designed to be seen close up and it destroys the illusion.

They sometimes have help with certain hair styles in principal roles and also for wearing wigs. Hair has to look perfect and last the performance.

Each dancer has their own ways of preparing their feet and shoes. Some apply pain relieving gels, before taping their toes, using cushion pads, folded paper towels or lambswool prior to putting the shoe on. Some dancers darn the platform of the shoe for better balance and durability as well as attaching ribbons and elastics.

Dancers also add Shellac, a kind of glue, to the inside of their show to harden it to last throughout a performance. Once I spilt a little water on the floor near some pointe shoes and learnt this could have affected their hardness.

Some swear by haemorrhoid cream for bruised toenails in between rehearsals and performances.

On entering the wings (which feels a bit like going through a portal to another world leaving reality behind) you need to be aware of cables taped to the floor, stage scenery, props with very little light to safely navigate. I’ve had a few near misses when walking around the very back of the stage to get to the other side and nearly walking on stage -the stuff of nightmares. I try to be as quiet as possible while carrying my camera and long lens, avoiding dancers flying off or about to make their entrance. The dancers are not quiet which surprised me at first, but the orchestra covers a lot of noise on stage.

I’ve since photographed Miki preparing for the dual role of Odette/Odile in Swan Lake, Princess Aurora from The Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella. I’m hoping that I’ll get the opportunity to photograph her as Juliet when it comes back into repertoire.

I’ve seen her nerves before the Rose Adagio in The Sleeping Beauty where she performs a series of balances en pointe; witnessed the pain of her feet as she strapped them and applied numbing creams; complete desolation after not achieving her main lift in Cinderella. She’s strong and fragile at the same time but always with the humility of an artist pursuing perfection.

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of Birmingham Royal Ballet. Miki Mizutani

Photographing Swan Lake from the wings again was very special. I also had better gear now to work in low light situations. I was mesmerized by the way the person working the dry ice machine worked the mist to sweep across the stage. Pure artistry.

Among my corps work has included the stars featured in Sir David Bintley’s Cinderella for Birmingham Royal Ballet and Frederick Ashton’s choreography for the Royal Ballet. Like the snowflakes, they appear briefly but are exceptionally beautiful. David Bintley’s stars have a tutu and headpiece covered in silver stars and they appear against a blue backdrop in the first act and a golden one at the end of the ballet. Ashton’s stars wear a very beautiful pale blue tutu, tiara, and carry wands that light up magically.

I remember talking to photographer Bill Cooper the first time I photographed Birmingham Royal Ballet’s Cinderella at The Mayflower theatre in Southampton. He had photographed the dress rehearsal and was also going to photograph the performance that night. He was to work at the back of the auditorium and had built a black box to silence the sound of his camera shutter. Now all photographers are expected to work silently in theatres, and this was the reason for my choosing to eventually go mirrorless.

I also remember talking to a new press officer at this photocall, and falling through the flip up seats spraining my wrist while quickly packing up my gear. I nearly nose dived to the floor but left with a little dignity intact!

I remember photographing English National Ballet’s The Nutcracker for the first time here in 2012, with Daria Klimentova and Vadim Muntagirov, and the fire alarm going off just as the snowflakes were making their entrance. Seemingly the dry ice had caused a problem. It was a November evening, freezing cold, and I remember exiting (with my camera) to stand on the fire escape with members of the orchestra.

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of Birmingham Royal Ballet - Mio Sumiyama, and Northern Ballet School - Sakura Iida

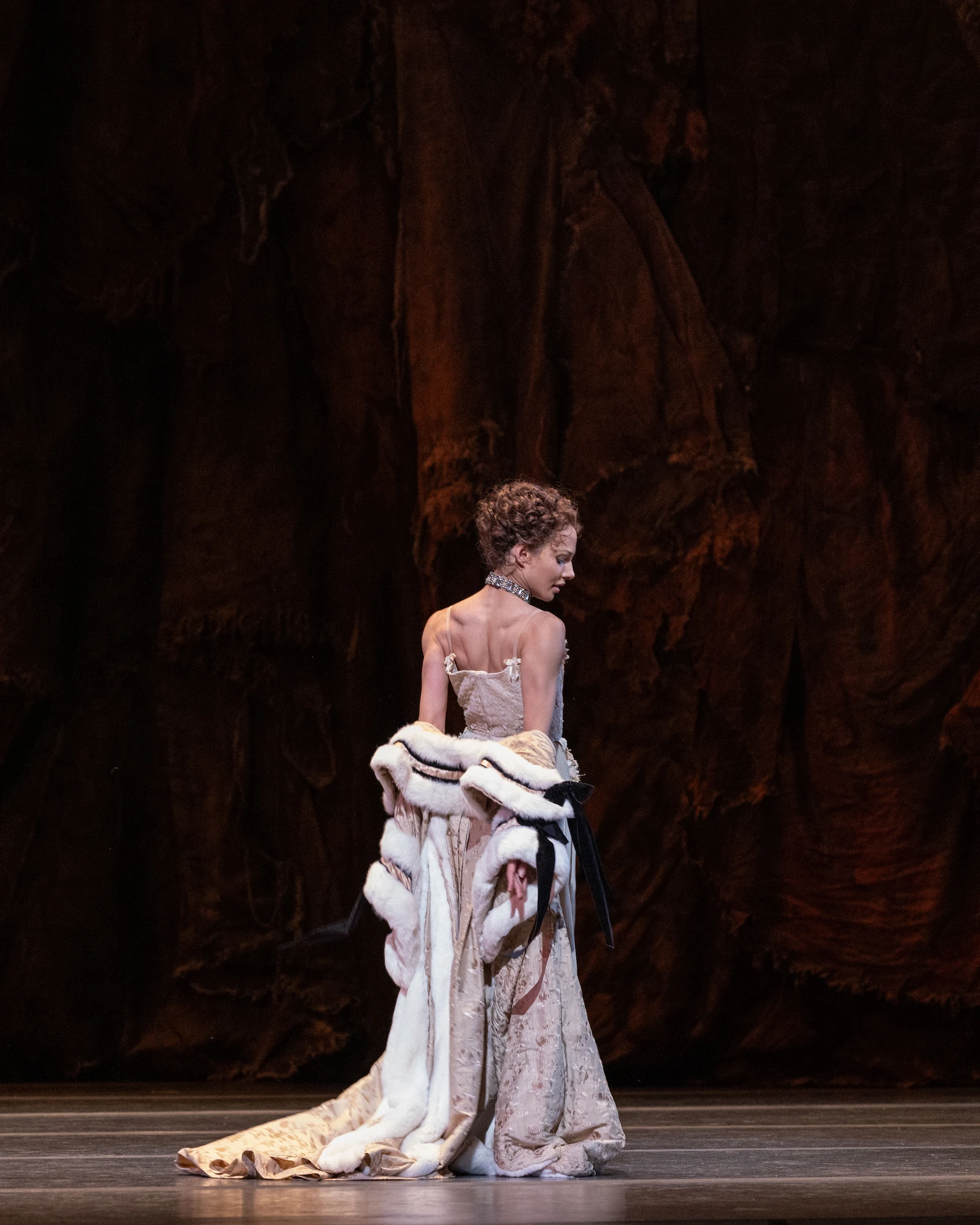

Over the years I’ve been desperate to photograph Kenneth MacMillan’s Manon. I’d repeatedly asked many companies that have it in their repertoire. And now I wanted to compare the characters of MacMillan’s Manon to Tindall’s Casanova, both sensual yet ingenuous characters set in the 18th century, victims of and responsible for their own fates. I saw that it was coming back into repertoire for the 2023/24 Season at the Royal Ballet to commemorate 50 years since it had premiered there, I wrote and asked again, and one very special person realised my dream.

Early the following year, I travelled down to London to photograph not one but three casts of this production. Francesca Hayward and Marcelino Sambé, Yasmin Naghdi and William Bracewell and Lauren Cutbertson and Matthew Ball. And I was to learn how different dancers interpret their roles, and also what good actors the dancers at the Royal Ballet are, often distracting me from the main action.

From arriving at Covent Garden tube station where posters lined the underground, to staying next door to St Paul’s (the actors) church and walking to the stage door of the Royal Opera House on Floral Street the following morning, was such a special time for me. Once I received my pass, I knew that finally I would be photographing this incredible ballet. Setting my tripod up in the auditorium, from which I had only seen once before on a backstage tour, and looking around at this beautiful theatre waiting for this devastating story to unfold on one of the largest stages in the world, made me feel so proud to be there. In the foyer were some of Manon’s original costumes, from when the ballet was first performed in 1974, and models of Nicholas Georgiadis’ stunning set design. This was to celebrate the centenary year of Nicholas Georgiadis’ birth.

MacMillan’s Manon, based on Abbe Prevost’s novel Manon Lescaut was written between 1697-1763, first published in Paris in 1731, and premiered at Covent Garden with the Royal Ballet in 1974.

Giacomo Casanova was born in 1725, and Tindall created Casanova a ballet of his life, that premiered at Leeds Grand Theatre in 2017 with the Northern Ballet.

Ian Kelly studied Casanova for years, wrote the biography Casanova, and became the dramaturg for the production. Casanova is described in the programme as, ‘Trainee priest and aspiring writer, polymath and musician. A man of vast intellect, creative and sexual energy, he is nevertheless plagued by depression and by an insecurity that the world may never take him, or his writings seriously’.

Now 50 years since Manon premiered, the theme of innocence corrupted by the need to survive in an avaricious society, is still relevant and contemporary even though it is set in 18th century France. MacMillan believed that design was absolutely integral to the identity and meaning of a choreographic work, and he worked with designer, Nicholas Georgiadis who set the ballet in pre-revolutionary France of the 1780s to reflect the precarious division between opulence and degradation.

Georgiadis was inspired by the Goncourt Brother’s Journal describing, ‘a picture of dereliction, with all its usurious exhaustion and tatty criminality, opening between burnt, ravaged, moth-eaten and rotten tapestry drapes . . . a sort of hole, full of bundles tied with string, piles of tow-ropes, unravelled silk and wool, a kind of cloth cesspit’. And he had the characters emerge on to the stage, through a cyclorama of rags cascading down the full height of the stage space, representing the poverty that divides the population of Manon from the beggars to the gentlemen, and how fragile the border is from survival and destitution.

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of the Royal Ballet. Francesca Hayward & Marcelino Sambé

The heroine’s struggle to escape poverty makes Manon one of the most dramatic and devastating of ballets. MacMillan said at the time, ‘Manon is not so much afraid of being poor as ashamed of being poor. Poverty in that period was the equivalent of a long, slow death.’ Her story is a battle for survival versus a desire for love. And while showing us passion, betrayal and unconditional love through his choreography, MacMillan clearly demonstrated how theatre is capable of dealing with all society’s concerns.

At the time of its premiere, audiences were more shocked by the fact that a woman could behave in such a sexually uninhibited way, and the question of the day was more feminist orientated depending on the dancer’s interpretation of Manon’s character. Antoinette Sibley, who the character was created on in rehearsal, saw her as a girl ‘who allowed it all to happen to her . . . I don’t think she’s a schemer – she only makes decisions when she has to.’ Lynn Seymour made her more ruthless and saw her and her brother as ‘cut from the same cloth, both bandits, using all they have to achieve what they want . . . she broke the rules and the punishment crushed her.’ Natalia Makarova understood her as an instinctive creature who lives for the moment, ‘extracting from it all the excitement she can. At the same time she fully knows that the day will come when she must pay the price . . . for the pleasure of living fully.’ And Sylvie Guillem’s Manon used her sexual allure to survive in a male-dominated world. And while other Manons died as desperate victims, limp as rags, Guillem fought on defying death itself.

Although well-received by the public, critics had reservations about the character’s motives, thinking Manon amoral. Mary Clarke wrote in The Guardian, ‘Basically, Manon is a slut and Des Grieux is a fool and they move in the most unsavoury company.’

An avid movie goer, MacMillan may also have seen the 1968 film Manon 70, directed by Jean Aurel and starring Catherine Deneuve, who is fashion conscious, free thinking and sexually liberated, challenging social conventions at the time.

MacMillan has been described as ‘the choreographer of ugliness, and abuse, and pain’, unafraid to tackle life’s darker themes, and dealing with them in the ‘safe’ environment of the world of ballet to powerful effect.

Jann Parry wrote in Different Drummer – The Life of Kenneth MacMillan that he took, ‘the damaged innocent, the vulnerable young person whose trust is betrayed. In many of his ballets, the key figure is the heroine, traumatised by events over which she has no control.’

On its 40th anniversary the Royal Ballet described Manon as an adult ballet. I see the characters as slightly older and more fleshed out than the more romantic Romeo and Juliet which he had choreographed nine years earlier. MacMillan described them as ‘instinctive and ruthless as rogue children’ but this does not make her a ‘Nasty little diamond digger’ or ‘deceiver and destroyer of the male’ as some critics claimed.

The themes of guilt and betrayal are displayed, with the inevitability in which people under pressure betray themselves and others. MacMillan made ballets about real life and conveyed emotional truth through the language of the body.

Manon is abused by her brother Lescaut, Monsieur Guillot de Morfontaine, and finally the Gaoler. For MacMillan to include a choreographic representation of enforced fellatio in a ballet was controversial and unsettling. Although I have recently sat in an audience with much older men who were not necessarily disconcerted. The same as listening to members of the audience choose which cast they pay to see based on the dancer’s attractiveness rather than talent.

We see the poverty at the very beginning of the ballet, as the beggars mingle with the demi-monde, and Lescaut forces his mistress to witness the tumbrel carrying the convicted women for deportation warning her that this could be her fate. The scene is set for Manon’s entrance and her story plays out in front of us.

We know MacMillan was inspired by the works of German dramatist and revolutionary Georg Büchner, with his portrayal of Woyzeck a decade later in Different Drummer, which shows the exploitation of the poor by the military and medical establishments of the time. He may have also read Büchner’s first play Danton’s Death set during the French Revolution detailing social inequalities and the need for political change, when Danton says, ‘The world is chaos. Nothingness is the yet-to-be-born god of the world.’

Professor Ian MacGibbon said MacMillan was, ‘a romantic choreographer, but one with a cutting edge – a classicist of the age of anxiety’

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of the Royal Ballet. Francesca Hayward

I find the presentation of Manon’s character on stage fascinating, as she seduces and manipulates the audience into forgiving her whims and misfortunes. I wanted to discover and capture the point in the ballet her emotions lift us beyond just feeling sorry for her to empathy. And this came in Act II, Scene 18 during a party at Madam’s house (a high class brothel) in Paris entitled ‘Manon and her admirers’. After a triumphant entry as Monsieur G.M.’s possession, she performs a seductive but strange solo with Des Grieux and Monsieur GM circling around her as the rest of the cast freeze, before she is lifted high and dispassionately passed from one man to another with one foot erect to make no mistake of Lescaut’s legacy for her. For this choreographic representation of manipulation and abuse, Massenet’s usually lyrical score becomes chilling, making the audience feel uncomfortable.

She was groomed for this. Her only education on how to please and gain the highest bidder. We saw the devastating results of disobedience in MacMillan’s ballet Romeo and Juliet almost a decade earlier in 1965 when Juliet refuses to marry Paris. Although set in Renaissance Verona, the situation Juliet finds herself in is similar, as her father makes clear that if she doesn’t accept and marry his choice of husband for her, she will be cast out of his house destitute.

For Des Grieux to castigate Manon when she receives jewellery and furs is hypocritical, as a gentleman studying to be a priest living off his family’s favour. Manon was travelling to enter a convent when they met because she had no means of her own, and would know that to survive an elopement, she would need riches to keep her from poverty once her beauty fades. She had no choice other than to be a realist and his educated ideals only serve to make her situation worse.

MacMillan chose a selection of pieces from the French composer Jules Massenet’s work, other operas as well as his opera Manon, oratorios, art songs and orchestra suites, with ballet pianist Hilda Gaunt. These were orchestrated by British composer Leighton Lucas and then reworked by Martin Yates in 2011 to unify and make it support the drama onstage further.

Yates said, ‘The romance and drama of Massenet’s music gave MacMillan the musical sound world that would reflect the drama of his ballet. It demonstrated perfectly his complete understanding of the function of dramatic music.’ This is fully realised with newly inserted haunting cello solo before the final act, setting the tone for the fourth heartbreaking pas de deux.

Tindall worked with American composer Kerry Muzzey, a modern classical and film composer, to create the original orchestral score for Casanova. For Kerry, approaching his first ballet, the challenge was how to underscore the life of the man that sounds like now. Tindall said that Kerry tailor made the music for every minute of the dance.

Capturing emotion in dance is not just about movement, but the dancers expressing their character and feelings. MacMillan became renowned for presenting emotional experiences like no other choreographer at the time.

MacMillan based the narrative structure of Manon on his previous three act ballet of Romeo and Juliet, and you can see visual echoes of the couple meeting in a crowded scene, Des Grieux declaring his love in a solo to a seated Manon. Their love story is revealed though a series of pas de deux including one set on a bedroom, and in the swamp Des Grieux desperately attempts to keep an exhausted Manon alive in a way reminiscent of Romeo’s disbelief that Juliet is dead in her family’s vault. The corps de ballet’s ensemble dances provide the social context to the story.

MacMillan is renowned for choreographing the pas de deux first, and the rest of the ballet after, and for capturing ‘emotion in flight’.

The dance critic Clement Crisp described MacMillan as ‘at his most persuasive as an erotic poet, exploring passion with images of extreme beauty.’ And the first bedroom pas de deux is joyously sensual, as Manon throws back her arms in abandon, to a besotted Des Grieux. The dancer Alessandra Ferri said how MacMillan taught her to stop thinking and just feel. But MacMillan’s narrative ballets have often been misinterpreted, as their main concern is not with sex, but with ‘the person destroyed by the social milieu’.

Manon’s first entrance in the ballet, as she steps excitedly down from the coach en pointe, is repeated in each act is a way appropriate to the world she finds herself in. In the second act she is presented by Monsieur G.M. at a party he throws in a courtesan house where he parades her around as his property. In the final act she can barely walk down the gangplank of the ship in New Orleans, and is supported by Des Grieux, before being appropriated by the Gailor for his use.

Des Grieux performs some of the most difficult solos and four pas de deux. Act III is a physically and emotionally exhausting finale, and MacMillan pushed it to extreme, with strenuous lifts and body flips conveying their emotional desperation.

MacMillan had planned a dream sequence as the prologue, but during rehearsals this became instead the opening scene of Act III, as a feverish Manon recalls her life.

Christopher Oram designed the costumes for Casanova, with the female dancer’s skirts openly deconstructed, giving the impression of courtly attire while enabling the dancers to move freely. Madame de Pompadour’s costume was particularly impressive, but Bellino’s (masquerading as a man in order to work as a castrato singer) was quite extraordinary, with her breasts bound to disguise her female form (We see her brother binding them at the beginning of the second act and Casanova releasing her from this bond at the end of their pas de deux), and her short breeches featuring a large codpiece.

Casanova’s costumes constantly change and evolve from a sleeveless priest’s cassock at the beginning of the ballet; to being given a golden outfit for his assignation with the aristocratic nun M.M.; a red coat from his benefactor Senator Bragadin; and a black leather coat following his escape from prison.

For Manon the costumes were often lavish, but the stench of poverty was to be ever present reflecting the precarious division between opulence and degradation. In the final act Manon disembarks from the convict ship distressed, in rags and her hair shorn.

Georgiadis researched 18th century paintings, and based the whore dressed as a boy in the brothel scene, on a portrait of Madam du Barry, King Louis XV’s last mistress, and the recurring sinister figure of the ratcatcher was taken from an etching.

Manon makes her entrance wearing a fresh looking pale blue gown at the beginning of the ballet; alights from the bed in her second pas de deux in a pretty petticoat with bows on the straps and ruffles of fabric, followed by the heavy luxurious fur coat and jewels presented by Monsieur GM; to a sumptuous black lace gown embellished with silver for Act II covered at first by an overcoat intricately decorated with more than 200 hundred bows.

Georgiadis created a heaviness of tone and hue with the burnt orange, dark brown and olive greens worn by Lescaut’s Mistress. The richness of these costumes is in contrast with the beggars resting by the coaches of the rich and sleeping at tables, emphasising the gulf between the haves and the have-nots.

In Manon, the lighting transformed the tiers of rags, (the ‘cloth cesspit’), ever present in the stage design of the first two acts, from resembling opulent drapes to dirty rags. Madame’s house while furnished with deep red drapes, chandeliers and mirrors shows signs of disrepair in the crumbling walls and ragged upholstery. The ballet ends with mist rising from the dangling strands of Spanish moss in the Louisiana swamp.

While Casanova’s set design was based on revolving pillars that could represent the church when lit by the chancel lamp, the golden ballroom, and backdrop to the nun’s quarters. Panels representing the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles were lit from behind to create different moods, and the set appeared to quite literally descend on Casanova while being questioned by the inquisition. Casanova was imprisoned without trial at the top of the ‘Leads’, the terrible prison area under the roof of the Doge’s Palace in Venice covered with sheets of lead. He and another inmate Father Marino Balbi escaped by making a hole in the ceiling and lowering down into the courtyard of the Palace. While miming his incarceration a shaft of light created the effect of prison bars.

In Casanova the audience witnessed the seductive nature of the church and also its danger to those who are not satisfied with its teachings; we’ve been dazzled by hypnotic masquerades; we’ve gamed with the great and good; met with people who questioned the times and looked for alternative answers to the universe they lived in; and what I am left with is a man who when he lowered his mask wasn’t accepted by the age in which he lived – until later when he truly had time to write of his own experiences leaving a vast and visual history of the time in which he lived.

To understand him, I think, is to see the man in context, and that is what Tindall has shown us so beautifully and memorably in a way that will always remain with me. Such an incredible team – the knowledge that Ian Kelly shared from his autobiography of Casanova’s life, Kerry Muzzey’s stunning score, the set, costumes and lighting designers, the staff who worked with Tindall and the dancers who breathed life into this incredible man.

MacMillan’s Manon endures half a decade later, with Georgiadis’ stage design for Manon constantly moving from rich opulent drapes, to degrading rags, and finally the dangling strands in the swamp, a lesson for us all, as we sit in one of the most beautiful opera houses in the world. While the ratcatcher haunts us as well as Manon, a reminder of those pushed to the extreme of their existence in a materialistic society.

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of the Royal Ballet. Francesca Hayward & Marcelino Sambé

I also visited the Freed shop at 94 Saint Martin's Lane, where I saw the steps leading down to the basement where Mr and Mrs Freed made ballet shoes for the dancers at Covent Garden, nearly 100 years ago. From humble beginnings in London’s West End, Freed of London was founded by cobbler Frederick Freed in 1929. Mr Freed and his wife revolutionised the dance shoe industry by tailoring shoes to a dancer’s individual needs.

I had previously visited one of the Freed of London factories in Hackney in 2016, to photograph the different stages of making pointe shoes. Here I learnt how the satin fabric was pulled over a last, and using a combination of paste, hessians and cards they built up the block to support the dancer’s weight en pointe. I saw the leather soles stacked up and how each maker has their own mark – a crown, heart, Maltese cross. There were reels of ribbons and cord, ballet and football posters, and one maker even used a reject pointe shoe as a phone holder. Hardly any of the makers have been to the ballet and yet they create the crucial item that breathes beauty into this artform.

Photography Caroline Holden, by kind permission of Freed of London

This craftsmanship is then partially undone as dancers often customise their pointe shoes. The internal felt is often stripped out and the shank nail removed for flexibility. I’ve also seen them beat new pointe shoes on the floor to break them in. After class and rehearsal you can see rows of pointe shoes drying out on radiators before a performance.

Dancer’s feet go through so much. Blisters are left to harden; bunions are common as well as bleeding toes. Once their pointe shoes are securely tied on, they make for the rosin box outside the door leading into the theatre wings, to rub their shoes especially the tip in to make them less slippery. Rosin is a resin derived from pine trees, and in a ballet company it arrives in chunks, that the dancer crushes with her shoe. Each company has different variations of this from cardboard to wooden boxes. Birmingham Royal Ballet also has a cheese grater embedded into one side so the sole can be roughened to create more friction when dancing on the stage floor. Rosin is also used by musicians who play stringed instruments, used in a hard chunk to rub their bows on for grip, tone and smooth bowing.